De-risking innovation

You won’t have missed that over the past few years an increasing number of charities are exploring how they can launch new fundraising or engagement products to reach new audiences.

Historically when it comes to developing new products the sector can perhaps best be characterized as adopting imitation strategies, rather than innovation. One charity tries something, others read about it or see a presentation about it at a conference, and before you know it others are adapting it and launching their own version of it.

We’re definitely now seeing the fruits of real innovation taking place with charities placing far greater importance on adopting established innovation methods and practices. What’s exciting is seeing innovation encompassing not just a new creative proposition but new business models, new ways of thinking about audiences, and the role of partnerships.

So let’s talk about risk. Real innovation involves risk, but then so does testing a new media channel or creative execution – the difference is two-fold. As a fundraiser, you will or your team will have developed a sixth sense around whether a new creative will work – and that instinct goes a long way to filter out potentially underperforming concepts. And the second difference is in the magnitude of risk. We’re now seeing innovative products, solutions, and services that require significant organizational resources and investment, so the anticipated regret of failure is so much higher.

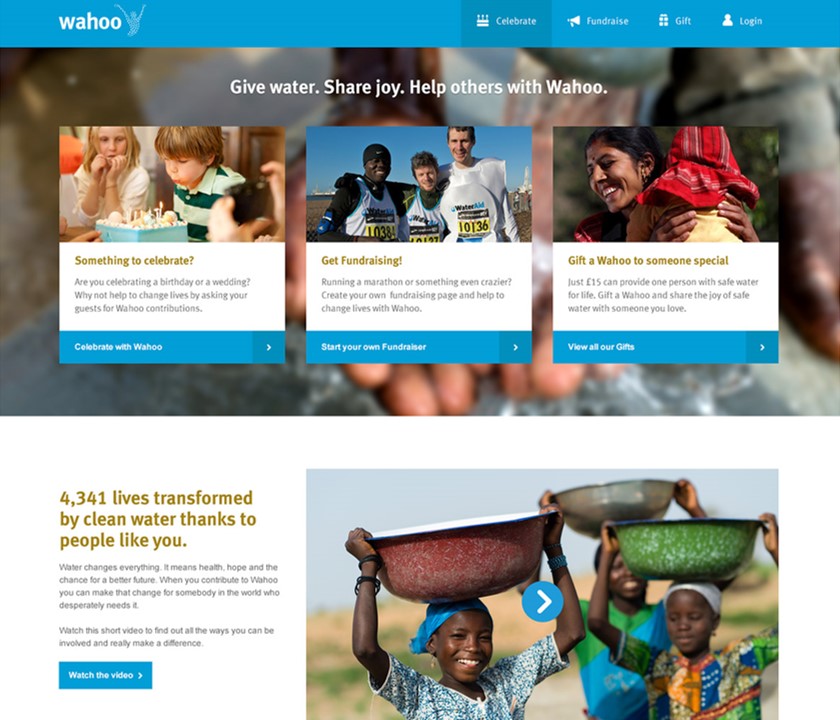

Many charities especially Overseas Development charities offer gifts in kind. The usual model involves someone buying a virtual gift for someone as a present. That person receives a certificate or simple letter explaining a donation has been made in their name.

Over the years this market become stale & WaterAid realised that the experience for the gift recipient was poor – a certificate not really creating the joy or warm glow a donation usually provides.

To create a distinctive alternative they switched the certificate for a story. So a gift of water was reciprocated by a powerful & uplifting case story of how water had transformed someone’s life.

Reducing risk

You can’t eliminate the risk entirely that the public won’t take up your new product in sufficient numbers to warrant rolling it out. But there are a range of practical actions you can take to get early warning signs that not all is well! This is the first of a series of posts looking at different ways to de-risk innovation, from relatively simple methods to more complex approaches that focus on using analytical techniques to interrogate new ideas.

This post starts with the simplest approach – the pre-mortum.

Idea #1 – the Pre-mortum

I’m sure we’ve all been to ‘wash-up’ meetings or review sessions where we’re asked to explore why a new campaign or product didn’t work as well as we may have planned. They’re uncomfortable, pretty grim, and often you leave thinking no one really got to the heart of the failure.

A ‘pre-mortum’ is an established way to discuss what went wrong before it’s even been launched to the public. As a group, you simply assume the project died an uncomfortable death and ask the team to come up with the reasons why.

This ever-so-simple method can work incredibly well because it tackles a major problem during the development phase of a project – that many of the team will be too reluctant to voice their reservations during the development phase. In my experience, the reluctance among the team to speak up is significant and amplified by three factors.

First, how ‘different’ the product category is for the new product. For example, launching a gaming app is different enough from fundraising to make even the most experienced fundraiser question what they can add.

Secondly, how much importance is being placed upon the new product or service – if it’s being held up as the ‘break-through’ product the charity has been looking for, then who among us would question the assumptions upon which the plan has been based.

And finally, the third issue that can silent voices is the level of buy-in from senior stakeholders. Getting the Chief Exec or Head of Engagement to push the idea is a sure way to stop people from expressing any concerns.

Here’s an example that succeeded in securing the media and public attention by disrupting the portrayal of the animals.

To celebrate Earth Day a French charity launched Pollupets – a range of animals that were damaged to reflect the harm done to them in a natural setting, such as a turtle being strangled by plastic waste.

This campaign tapped into a growing market for baby and toddler soft toys that are designed as broken or imperfect.

By pretending the project has already failed you’re no longer asking the team to speculate on what might happen, but to imagine what has happened – and it’s this certainty that makes all the difference to the quality of the explanation.

One of the key benefits of using this method is that it encourages everyone involved to look at the planning from multiple angles. The idea is to come up with a long list of potential problems and then find ways to avoid these problems by making sure they won’t happen in the first place.

The Pre-Mortem method can be used to break the ‘group think’ mentality which occurs in some groups. If everyone in the group shares the same mindset, it can be difficult to see beyond their shared assumptions. By asking everyone to consider the worst, it prompts them to think about things from a different perspective and therefore come up with new, innovative solutions.

The organisational change academic, Karl Weick, argues that the pre-mortum is helpful as it helps people bridge short-term and long-term thinking. He argues this shift is effective, because it is far easier to imagine the detailed causes of a single outcome than to imagine multiple outcomes and try to explain why each may have occurred. Analysing a single event as if it has already occurred rather than pretending it might occur makes it seem more concrete and likely to actually happen, which motivates people to devote more attention to explaining it.

Another key benefit is that it gives people the space to be critical without undermining someone’s confidence or making them feel uncomfortable by pushing them out of their comfort zone – in a sense ‘there are no stupid questions’. It pushes all team members out of their comfort zone, which means that nobody feels singled out. In addition, because everyone has had an opportunity to share their views and be given time to reflect on these, it’s more likely that people will commit to the plan and be prepared to go along with it.

The final benefit is that this approach tackles over optimism. Most people overestimate that things will go well, and underestimate that the project will go badly. By establishing that it did in fact fail, it goes some way to eliminate over optimism and gives voice to those who were already pessimistic but didn’t want to say anything in fear of recrimination or being seen as out of step with everyone else.

An example from 2014 of one of the first subscription box products from Child.org. The Blurt Foundation launched ‘Buddy Boxes’ later that year.

Steps to running a Pre-mortum session

The Pre-Mortem method is relatively simple to use and can be applied to almost any project or task. The only real difficulty comes in overcoming what Kahneman calls the ‘focusing illusion’ (which involves overestimating the importance of whatever we are thinking about at any particular moment). It’s important to be aware of this bias so you don’t fall into the trap of focusing your preparations on just one potential problem.

#1. Create a shared view: Start by gathering your team and asking them to read a two-pager outlining the proposed product or service – what it will do, for whom, how it will work etc – using a business canvas can also be help.

#2. Imagine the worst: Explain that the project has taken place, and has been a complete disaster. Don’t say it fell short or underperformed– tell them it failed in a big way!

#3. Generate Reasons for Failure: Ask each person to write down on post-its all the reasons (one post-it for each reason) they can think of to explain the failure that occurred.

#4. Share Reasons for Failure: Ask each person to share one item on their list and continue to go around the room until everyone has exhausted their lists.

#5. Gather and group: Gather all the post-its and group them into topics, such as ‘assumptions’, ‘strategy or ‘execution’ – alternatively group them by campaign feature, such as ‘price’, ‘audience’ and ‘competition’.

#6. Brainstorm with solutions: Go through the topics and discuss solutions to prevent the issues from happening. For instance, if the issue is ‘audience response’, ask how else can we forecast demand.

#7. Review the list: After the session, review the list and look for ways to strengthen the plan.

Recommended reading

Back to the future: Temporal perspective in the explanation of events. Journal of Decision Making

Main Image – Story Shop by World Vision

Words by James Long

Next time

De-risking Innovation through a Red Team