Oxfam inclusive language crises

In 13 March, Oxfam’s UK headquarters shared an inclusive language guide with its employees with the aim of “supporting and empowering everyone they interact with in the course of their work to feel included”. But despite Oxfam’s good intentions, this guide, when made public, generated a great deal of controversy in the UK.

We wanted to analyse the impact, to see what influence this crisis had on Oxfam, in terms of brand health and on its digital audience.

The set up

To analyse the impact of a brand health crisis, we conducted a Social Listening analysis where we measured the volume of conversations, positive and negative sentiment, and the impact of certain influencer profiles on the conversation around the issue.

We carried out the analysis on the social network Twitter, as it is the network that allows to collect more data than other social media platforms. And more importantly, because it’s the network where users express themselves without the social containment that they impose on themselves in other networks.

In contrast Facebook is the network usually used to interact with family, friends and even work colleagues. On this network it is rare to find harsh criticism or heated discussions. Instagram and TikTok are networks where a positive image predominates, so aren’t the natural platforms for an overly critical topic either.

Although there are exceptions in all networks, we can say that Twitter is the most used network to express criticism. Plus Twitter allows us to identify the type of profile of the different digital audiences involved – critical for social listening.

How do we measure “volume” in a digital conversation?

As in any conversation, “volume” influences the impact on audiences, and to measure this we use mentions, interactions and engagement.

The quantity of mentions a topic generates is a good indicator of interest shown by the audience. The same criteria can be applied to interactions. These KPIs do not allow us to interpret sentiment, but they do give us a measurable measure of interest.

What did we find?

Mentions

The total volume of mentions of the Oxfam guide was 9.8K mentions. This is an increase of 6,800% compared to the 30 days prior to the publication of the guide. The increase in such a brief time helps us understand the impact the publication of the Oxfam guide has had on the digital conversation.

Total Interactions

As with mentions, this helps us understand the relevance of this conversation in the digital environment. As well as generating more comments towards the brand, it has also boosted the engagement of those posts.

Potential reach

When talking about the impact of the online conversation in terms of reach, we can see that its influence has exceeded 2M potential impacts, which helps us to understand the repercussion of this topic. High impact users, (whose posts reach a relevant number of users), have participated causing increased visibility and enabling a larger audience to engage in the conversation. This reach, as with the rest of the metrics, has experienced a significant increase of 119%.

Evolution of mentions

Although the guide was launched on 13 March, it took a few days for it to become known to the general audience. The highest peak of mentions occurred just a few days later from the 17th to the 18th of March, which is when the media and relevant figures in the UK echoed and shared their opinion on social networks, provoking a wave of responses and visualisations, acting as a true amplifier of the news.

During that 2-day peak 5.2K mentions were made, 53% of the total conversation.

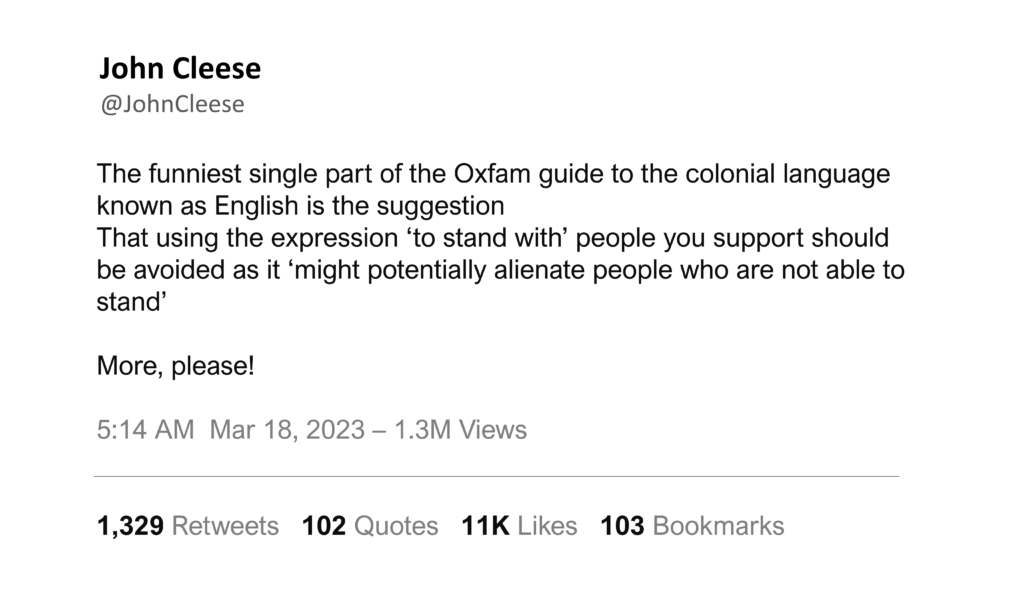

As for the amplifiers of the conversation, we have two noticeably clear actors: the television programme Good Morning Britain and John Cleese .

During a GMB show the guide was widely commented on, and all the participants gave a negative opinion about the guide. They went as far as to refer to the Oxfam guide as “scandalous” or “is this a joke?” And making allegations aimed directly at Oxfam’s donors: “this guide has been made with donors’ money, instead of investing it in more important campaigns”. Meanwhile John Cleese tweeted that he was offended that the guide implied that English is “a colonial language”, and that certain expressions, such as the word “support”, should be used with caution.

Measuring sentiment

Social Listening tools not only allow us to measure the impact of a specific topic, but also the sentiment that the audience has about it. Perhaps unsurprisingly the language guide generated mostly negative sentiment, with almost 80% of the total conversation being negative.

The main reasons for these negative comments are related to the following topics:

- The advance of “culture woke/culture wars” in society, and the consideration that race/white privilege dominates all strata with the consequent need to include other groups.

- The reframing of the terms “father” and “mother” to accommodate non-binary or trans people who would not be included in the meaning of those words.

- They allude to Oxfam’s recent past in Haiti to invalidate their arguments for inclusion and ask that their donors’ money go to nobler and more necessary causes than the inclusion guide.

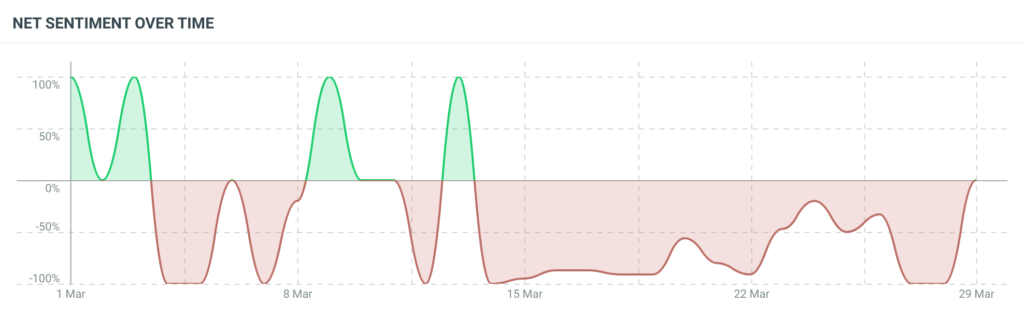

Net sentiment over time

Digging deeper into the digital analysis, to focus on a given period, we find a net sentiment with two distinct periods of negativity. The first was found a few days before 8 March, Women’s Day, where some users were already showing resistance to Oxfam’s broader and more inclusive concept of what it means to be a woman, including transgender women.

This first spike in negativity is not caused by the inclusive language guide, but by a rejection of the values that Oxfam espouses on Women’s Day.

The second volume of negativity, which lasts until the end of March, is found after the publication of Oxfam’s guide to inclusion, where comments are unleashed against how inclusion is approached from a culture of progressivism, which in the opinion of critical users is wrong and goes against their deeply held beliefs.

The first volume of negativity indicates that several Twitter users were already critical of Oxfam prior to the publication of the guide. However, we can see that the controversy caused by the guide lasts longer than the controversy caused by Women’s Day. The increase in temporal impact is explained by the successive sharing by media profiles and influencers. Each of these increased the visibility and impact of the issue, which caused a greater permanence in time.

The characteristics of the critics

To better understand the impact, its causes, scope and to be able to identify the most appropriate channels and content to respond to a controversy of this kind, it’s necessary to analyse the profile of the users.

We analysed the gender and age of the critical profiles, but also of the profiles that supported Oxfam.

Those who have shared a negative opinion of Oxfam’s guide on their networks are mostly men in the 25-34 age group. This group has been the most reactive to the issues addressed in the guide: feminism, Britain’s colonialist past and its influence on language, transfeminism, and inclusion at all levels of society.

The age group is a particularly important cohort, given that this, in percentage of participation in the conversation, is double that of the next age group 18 – 24 years, which is the generation that was born with social networks and therefore has a greater penetration in social media. They have, compared to previous generations, a greater facility to interact and share opinions on their social networks.

In principle, we should see more activity from the younger age group, but the 25-34 age group has become more active in this area.

Why are those aged 25-34 more active and critical?

The 25-34 age group is the generation that is entering the world of work and is starting to take on parenthood as well, or at least is already considering having children. This could be reflected in their personal priorities and how they see the world. The guidance and the “noise” that has been created around the opinions is perceived by this segment of users as an attempt to break with the patterns they consider correct, and an “ideological imposition” with which they do not agree.

A 34-year-old may not have been born with social networks at their peak, but they have lived the Internet since childhood and are used to using social networks. When an issue “touches their heartstrings”, they also express themselves on social networks, just like younger people.

Gender Pronouns

In relation to the gender pronouns with which the audience identifies itself publicly, we have a group of audience members who recognise themselves as women and cis men. This goes hand in hand with them having been reactive with a guide that accommodates the inclusion of non-binary or trans people.

This insight may help to guide the content of subsequent communications and how to deal with certain topics, such as family, parenting, and motherhood. Knowing that a large part of a certain audience proactively identifies as female, while another part of the audience does not give importance to gender identification, because they take it for granted, can be helpful when establishing a communication strategy.

What other metrics can we measure?

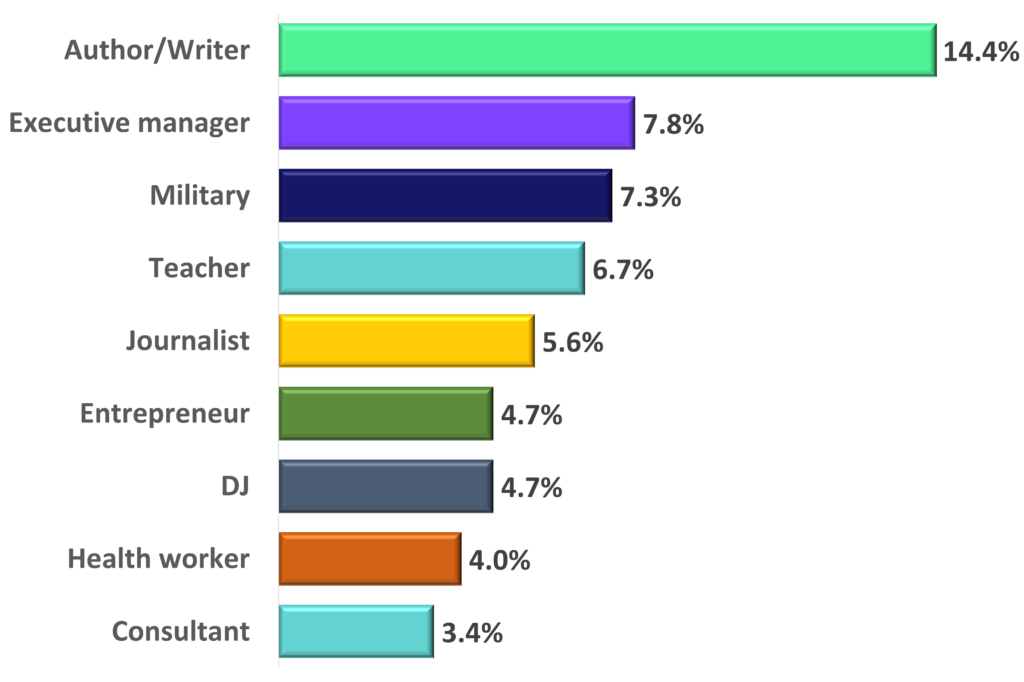

Social Listening analysis also allows us to know the interests and professional occupations of the participants in the conversation.

These data are provided by the users themselves when they publish their interests and professions in the profile descriptions. This data is not 100% reliable, because some people exaggerate in their profile description and others may change their interests and profession over time, but do not update their description.

However, it is a data that allows us to understand the audience a little better and it allows us to make a particularly useful classification for content creation, channel, communication, etc.

About this audience

In this case we were able to detect something quite enlightening, as their main interest is Family and Parenting, which tells us why they would be so critical about the suggestion of not using the terms “father” and “mother” or being more inclusive of trans or non-binary people who choose to parent and do not identify with these terminologies.

This audience have a conservative view of the family and how society should be shaped from a more traditional point of view.

The interests, as a whole, show a picture of a family-loving, animal-loving audience, interested in sport, literature, science, and music. More ‘superficial’ interests, such as leisure, food, and drink, come last. This knowledge could be used by Oxfam to develop content and messages related to parenting and the role of the family in the projects it develops, to connect better with this audience.

Influencing a digital audience

An influencer is a profile with a wider reach than the average user. It is someone followed by many people and who may have a certain capacity to “influence” the behaviour of their followers.

In a marketing campaign, many brands opt for a influencer marketing strategy, for product placement, promotion of services, or increasing the visibility the brand image itself. But in a “digital conversation” there are also influencers who can influence behaviour, even if they are not acting under contract. An “influencer” in this case could be a celebrity, a journalist, a media profile. Obviously, it is necessary to have many followers to get the status of an influencer.

In this analysis we have tried to identify the authors of messages with the greatest relevance and reach.

The negative influencers

Through the analysis of the authors of comments and messages that have experienced the most interactions, we see how strong the exposure and reach of negative comments about the guide is.

Among these authors we identify major British media and society figures, many of whom have the blue Twitter tick, which helps to increase their influence on the network that most amplifies this issue, Twitter.

The support of these amplifiers, with a greater reach than usual profiles, has meant that negative opinion reached much further and has had more visibility than it would normally have had.

We can conclude this by comparing the temporal duration of the reach of the peak of negative sentiment generated around 8 March, Women’s Day, and the much longer negative peak of the critics towards the inclusive language guide.

The greater reach of these influencers has allowed a topic about Oxfam to engage users who neither follow Oxfam nor have any interest in the charities work. Despite this they have participated in the conversation, contributing their negative or positive opinion.

The main concerns of these influencers relate to defining the English language as a “colonial language that needs to be redefined” and that the words “father” and “mother” may be offensive to other groups, what these influencers perceive as a way of erasing the presence of women and mothers in society.

Influencers are not only giving their opinion, but also trying to influence Oxfam directly, being conscious of the impact of their messages. One of the influencers, Renée Hoenderkamp, has gone as far as to say on her networks that she was an Oxfam donor and that, because of this guide, she is going to stop donating. The implied warning to Oxfam is obvious – if she stops donating, her followers might do the same. While it is not known if she is or has ever been a donor to Oxfam, her message could have an impact on a donor to Oxfam.

We conducted the same analysis on the digital audience that spoke positively about the inclusive language guide.

The positive audience

In the case of users who refer to the guide in positive terms, we see that most of the participants in the conversation are, on the contrary, women. That said, the difference between women and men is narrow, which indicates a greater homogeneity of opinion and support for what the guide advocates.

With age, something similar happens, the population group with the highest percentage is the 25-34 age group, but the difference between the different age groups is much smaller than in the case of negative comments. This data indicates that there is stability and closeness between the different generations regarding the positive opinion on the issues addressed in the inclusive language guide.

Gender Pronouns

For gender pronouns we see a comparable situation as with the other metrics. Among the positive comments and support for inclusive language to accommodate all people, we see a broader and more inclusive demographic, with users of different ages participating, a greater gender balance, and a wider range of pronouns, including non-binary people and their pronouns they/them or they/she

INTERESTS

In terms of the interests and occupations of those commenting positively on the Oxfam guide, we see that their main concern is related to literature and books, and they show a greater inclination towards education-related issues as a percentage than those who commented negatively. This helps us to understand that literature, culture, or art, with all that it entails: valuing other realities or curiosity about different stories, can be important for this group. In third position is Family and Parenthood, although they may be more inclusive in their approach than the other group. The recommendation to include information about family and parenthood in Oxfam’s publications, campaigns and projects would help to connect with this group as well.

Which influencers support Oxfam?

In the case of the top Influencers in the positive comments we see that Twitter is also the main medium where the conversation has taken place.

The main difference with respect to the other group is the absence of spokespersons with influence and impact on British society, who give voice to another discourse so that it reaches more users.

Those who have shared their opinion are mostly part of the transgender community, thanking Oxfam for their courage and commitment in sharing this guide that they say defends the freedom and reality of many people that non-inclusive language leaves out of their margins.

To be able to achieve equality in terms of visibility and impact, Oxfam can find powerful voices from both users and media that advocate for language where all realities must be considered to move towards a fairer and more equitable society and to be more relevant in the digital environment

Responding to a brand crises

This controversy has been geo-localised in England, where Oxfam made the guide public and where the media, by publicising it, acted as amplifiers, increasing the participation of other users in the digital environment.

Many of the negative opinions are based on a lack of knowledge. Many of the users with negative opinions stated that they had not actually read the guide, so that their statements were already based on an unrealistic or distorted context.

One of the central axes of the controversy, that Oxfam considers English to be a colonial or oppressive language, is based on a statement never made by the organisation.

This makes it exceedingly difficult to steer the conversation towards points of convergence, but the scope that the issue has become may be an opportunity for Oxfam to develop objective communications about what it has sought to convey in the guide and to give a realistic view of its objective in making these recommendations.

Oxfam first asserted positivity in its fight for inclusion:

And a week later Oxfam launched the campaign “This F … Word is more than offensive”, this F word is more offensive, playing with the usual English interpretation of “F … Word”.

The campaign refers to FAMINE, a problem affecting people in the Global South, but is receiving less and less air time in the UK media.

Through this twist Oxfam manages to turn the conversation around, to put the focus on what really matters. It sends a clear message: “while you argue about words that no one has said, there are real people, men, women, children and whole families, dying of hunger”.

3.- Street Marketing vs Online Marketing?

Oxfam has gone one step further and crossed the digital boundary to campaign on the street.

The controversy over the language inclusion guide was confined to the digital environment and the media. This “F… Word” campaign was launched both in the digital environment, media and on the street, through very striking Out-Of-Home actions.

With bus shelters, cars with posters, screens and even illuminating emblematic buildings.

With these actions, Oxfam not only changed the topic of conversation, but also regained the initiative of the conversation and was able to take centre stage in the media to focus the debate on the work and objectives of the organisation. This time not on the basis of mentions by journalists, but in person.

Developing communication strategies

Future communications can consider issues such as family, motherhood, and fatherhood, to incorporate them into a point of view that is more appealing to more conservative sectors.

This could make it easier to connect with people who certainly do not want anyone to starve to death, but who react more easily if the problem is explained to them from a point of view that incorporates concerns, they have: the family, for example.

In other countries, such as Spain, Italy or Germany, there could be a similar reaction if Oxfam shares this guide, and it is picked up by the media or a group of influencers.

It would therefore be advisable for the organisation to prepare a communication strategy in advance to deal with the controversy and negative comments that could be generated.

In the specific case of Spain, it would be even more of a priority considering that the debate on inclusive language, transgender rights and the reality of non-binary people has already generated a major debate, with laws in favour and currents actively against that have produced a lot of polarisations in society.

Words by Marina Fernandez.

If you’d like to know more about how Social Listening can help you understand your audiences we’d love to hear from you. Please contact us here